I’m beginning to think point and click games are like busses. I’ve gone without playing one for years, and then in the space of a week two come along at once. Although to be fair, that seems a bit too regular for a bus services, especially here in London. The latest offering is Lumino City from the guys and girls of State of Play, and it’s turning out to be something special indeed.

I was lucky enough to have a sit down with the head of State of Play, Luke Whittaker, and co-founder Katerine Bidwell for a rather informative chat about Lumino City. Of course, I’d been living in a bubble of point and click ignorance for a while, so knew very little about the project. Luckily, Luke was more than happy to get the ball rolling:

• Developer: State of Play

• Publisher: State of Play

• Reviewed on: Windows PC

• Also Available On: Mac

• Release Date: December 3rd 2014

Luke Whittaker: The game started off as Lume, which came out in 2012 and was done for a very low budget in our free time or whatever we could spare. Lumino City is the sequel and the intended grand story.

It was filmed by hand, and everything you see in the game is hand built. We wanted to tell the story of an entire city, and we couldn’t do that straight off because there were so many technical challenges so we thought ‘let’s focus on one, little, small place’, and that’s what Lume was. And that received such a wonderful reception that we thought ‘ok brilliant, let’s go for this grand idea’, and we’ve gone all out with it.

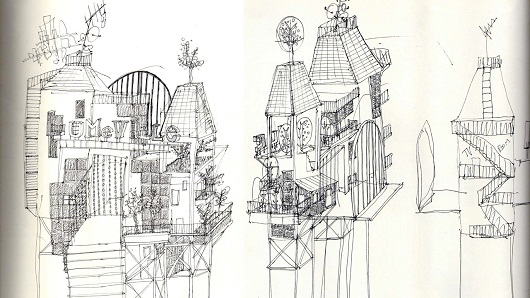

We’ve been ambitious in every single way. We’ve worked with architects to come up ideas and design the buildings, and we’ve used architectural techniques, such as using laser cutting for the models. Even during the sketching process we did things like make cardboard models out of sketches, which is what they did to make very rough versions, and used prop designers to design these grand things. The city actually stands about ten feet tall, and it’s all full of motors. The city actually works.

I have to say, it looks like a model you would see in a Wes Anderson movie.

Katherine Bidwell: That’s a big complement, he does some amazing stuff. Everything you see on screen has been handmade, even the characters are handmade and animated afterward.

LW: It’s been important. It’s part of the fabric of the whole thing. It’s not just a style that’s placed over the top, the whole atmosphere of the world and the feel of the place is tied in with the story.

So everything complements each other?

LW: Exactly. You can’t get this kind of feeling if you went about it with 3D software, or if you did you might need ten years and two hundred people. Even then it would be different because it’s two hundred people whereas with Lumino we’ve managed to keep everything very close to the original artistic intention. We wake up we go ‘right, we need to build a station in the sky’ for example, and that’s a difficult concept perhaps to maybe spread around and work on with a huge team.

I can imagine with a smaller team it’s easier to keep the soul of the project. It’s still got the heart that it had when the idea was first conceived, and that can get lost along the way with a bigger team.

KB: Yeah, precisely. It’s almost sort of engrained in what we do. Even now when we’ve been tweaking stuff we’ve been like ‘oh no, that’s not part of Lumino City’. It’s like we all instinctively know how the game should look and feel, and when it doesn’t feel like that it’s a real jar.

LW: It just improves the project. The way we approached it is to create a wonderful place to work and a wonderful way of working, and that has kept us going. It’s been three years, and we didn’t think it was going to be three years, but we’ve enjoyed it, and that’s kept the quality and the enthusiasm.

And that fun and enthusiasm you share shines through in the quality of the game?

LW: Exactly, and that’s true with everything. In every office you want everyone to be working at their best, and that’s the way it is at the end of this three year project. We’re in the process of refining everything.

We’ve tried to do away with the frustrations of a lot of point and clicks. We’ve kept things making logical sense so if you want to look in your bag, you click on your bag, and you can’t pick up anything that doesn’t fit. We’ve done away with all interface and tried to make it as intuitive as possible. This is the next stage of point and clicks where we’ve gone beyond the clunkiness of the pickup/use mechanic. You don’t need anything but a pointer.

KB: We wanted everything to make sense and not be a kind-of-random ‘this flag on this building makes this’ sort of thing. Even though it’s not real world, we want it to feel like ‘ok that lock doesn’t work, I need a spanner’ or something like that.

I have to admit, I’m a little bit in awe of the visuals. What made you decide to go with this style, what was the main influence for it?

KB: We’ve been running State of Play for about eight years, and our backgrounds are interactive; media and games. We’ve always been naturally happy with a sketchbook, drawing things. Even in those early days when we made browser games we’d always sketch things first and scan them in, so we were quite old school with that I suppose. Using mixed media and things. It kind of became a natural progression. We had this idea for Lumi [the main character] and lots of different things, and we wanted to think about how she’d look natural in the scene, and Luke suggested we make a model and take a picture of it and see what happens.

LW: I think we started by experimenting with drawing on the computer and then overlaying paper textures, and that was fine, and it looked nice, but also I thought ‘this is sort of cheating, why don’t I try and make them?’

KB: Digital SLR’s look really good, so we were like let’s just take a picture, and Luke put it in flash and photoshop and had Lumi running across this background of trees and stuff, and it just looked really good and we thought maybe there’s something here.

LW: It’s like you were saying about with a small team you get more soul into it, there is such a short distance between our intention and that because it’s physically there in front of us. You’re basically getting rid of too many technological barriers. If you start with a blank 3D Studio Max project for example, there’s a lot you’ve got to put in to that.

KB: I think that would be the most daunting thing for us. Take lighting for example, people say to us ‘what lighting programme did you use?’ and we’re like ‘we turned a light on’. To us it feels like the most natural way to make something look the way it looks in your head, the way you want it to look.

LW: It’s the most fluent way of communicating definitely, and this is what should be coming out of the screen, as well something more immediate.

KB: We feel like you get a layer of soul in it that you struggle to get any other way, and it’s important to get that across. The game took a long while to develop, but it would have taken even longer for us to communicate what we want a different way.

LW: That’s the thing with being conscious of what we’re making. We didn’t just launch into it and say we’ll make a game out of paper and card and that’ll be enough, we wanted to give it a certain graphic style as well. Plasticine was out as there’s nothing gelatinous in that. I wanted these to look iconic, like if they were printed out on a poster, or screen printed side on you could recognise them straight away. So everything is built of geometric shapes and taken from an angle which is memorable. There were certain rules like that and a certain language we developed that probably comes from pop-up books.

We actually made a game based around a pop-up book first, that was one of the games where we were overlaying paper texture.

How long did the animation side of things take?

LW: Two years. The game is eight to ten hours long, so it was like animating an eight hour film or something like that, and hopefully it shows. Everything is handmade, nothing has been off the shelf. Sometimes with animation, if you’re using stock animation, you’re going to get clipping problems and things that break. We’re not using that.

KB: In terms of animation, everything’s bespoke, there were no short cuts with this.

As a genre that seemed to have died out a few years ago, only to see a resurgence lately, what made you decide to make a point and click?

KB: We’ve always loved point and click games. We’re from a generation of Day of The Tentacle and Monkey Island, so everything’s sort of influenced by what we know. There was a real love for it and I never really of understood how it was out of favour. I’ve been playing Professor Layton on the DS and and there’s a real love for it again, and I think the way puzzle adventure game take you through a narrative is really special, and a game where you can take your time and work things out just ticked all the boxes for us.

LW: We love stories. There’s been a fashion for 3D and first person, and that limits you to one kind of story telling in a way, and you end up with narrative problems like ‘what happens if someone’s talking to me and I look at the corner for a while ‘. It’s a whole different language we’re trying to deal with, it’s a really fluent way of telling a story, and the fact that families love this, and parents and people come up to us and say ‘I don’t play video games but I’m going to buy this’ really validates it. Everybody loves stories.

KB: We were at GameCity and this family came back the next day to play it again. They’d been once before the previous day. There was a dad and a five year old and they were all like working it out together and I was just like ‘this is why I make games’, and this is why I want to continue to make games, so people can do that. Games obviously get a bad reputation, but it’s the most natural and creative way to tell a story and to get the whole family involved. I really hope that we offer that in some way and that comes across in how we’ve made Lumino City and what it’s about.

[vimeo id=”97832046″ align=”center” mode=”normal” maxwidth=”530″]

Official Game Site